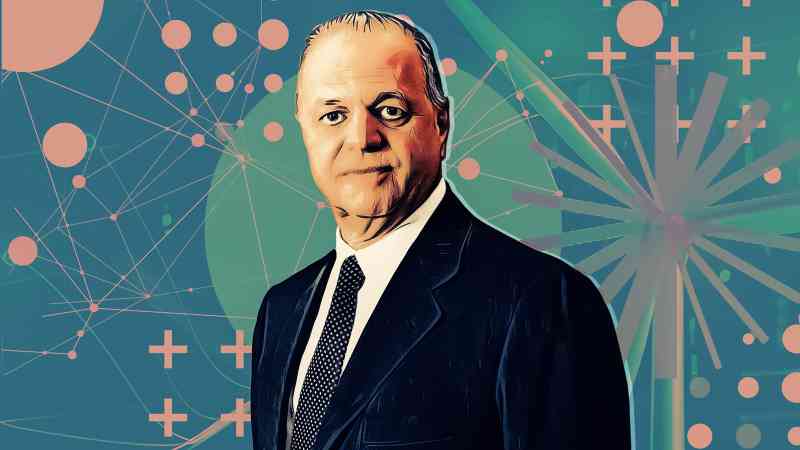

Evangelos Mytilineos could sense something was up. The Greek energy and metals magnate had assembled a team of 25 investment bankers to advise on listing his family’s eponymous conglomerate, Mytilineos Holdings, on the London Stock Exchange. But at the end of the meeting, the financiers looked sheepish.

“Mr Chairman, can we go upstairs and have a chat about a more personal issue?” asked one, nervously.

“A personal issue? With investment bankers?” laughed a confused Mytilineos.

They traipsed awkwardly up to his handsome personal office — a vast open space with abstract sculptures, flashing television screens and a private veranda canopied by pomegranate trees, looking out on the imposing Athenian mountains. Gathering by a polished oak table, one banker tiptoed around the delicate issue.

“You have a great name. And we know that in Greece it is a very famous name, very traditional,” he said. “But this name in English is very difficult to pronounce — you cannot be a FTSE 100 company with this name. People will have difficulty telling their brokers what stock they want to buy.”

Mytilineos knew the bankers had a point. So, in June, he grudgingly decided to change the family firm’s name to Metlen, a portmanteau of metal and energy. Old habits die hard, though: throughout our hour-long interview, Mytilineos mistakenly refers to the company as “Melten”, and his business cards are still debossed with its old name.

“I need to get those changed, I suppose,” he grins.

Sparking the interest of UK investors is top of Mytilineos’s priorities as he tries to pull off one of the biggest floats on the London market in recent years. The Athens-listed Metlen Energy & Metals is the largest home-grown company in Greece and generates about €6.35 billion (£5.44 billion) a year, mainly from building energy infrastructure, such as solar and wind farms, and mining for aluminium. The relisting would also be a boost for the FTSE, which has had to contend with a famine of floats and a US exodus over the past year.

We meet at the company’s headquarters — a grey, sprawling complex that looks more like a military base than a corporate office — in the northeastern Maroussi district of Athens. The site has been the company’s home since 2019, but it will be replaced next year with a London headquarters.

The chief executive and chairman is dressed business-casual, wearing a crisply ironed pale blue shirt stitched with his initials on the left of the midriff. In the sweltering Athenian summer, his sleeves are rolled up. As the largest shareholder in the £4.7 billion company, his personal stake is worth around £850 million.

A cerebral type with the air of ageing academic, or diplomat, Mytilineos pauses for several seconds before answering each question, looking into the mid-distance to conjure up an answer. “My hobby is geopolitics — I could talk about it for hours,” he says at one point.

The company he runs employs 6,500 people across 40 countries including Britain, Australia, Chile and Canada. Its energy business, which accounts for two thirds of revenues, builds sub-sea energy cables, solar parks, wind farms and grid connections. It also operates an energy trading business. Metlen’s metals arm is among the world’s biggest producers and exporters of aluminium and alumina, which is mined in Greece, and is working on producing rare earth metals used in semiconductors.

The UK, where the company has £2.15 billion worth of contracts, is one of its biggest markets. Earlier this year, it struck a £1 billion deal to build parts of a sub-sea cable link from Scotland to Durham that will carry enough renewable energy to power two million homes. It is also building gas power plants for energy giants Vitol and Drax in England and Wales, and is constructing what will be the largest solar farm in the UK in Kent, providing enough power for 100,000 homes.

Metlen is the second-largest retail energy provider in Greece, behind the state-owned incumbent, and now it wants to grow its UK operations after the London float. Mytilineos, 70, hints that it may one day try to disrupt the UK market, including Octopus Energy. “We know the business. We have the know-how … We can do the business.”

The relisting will also require Metlen to be squeaky clean with regulators. In 2018, Mytilineos was accused of corruption over allegations that his company paid authorities to secure a contract. He was acquitted the following year and the case thrown out. The chief executive reveals that Metlen is now compliant with 80 per cent of the UK’s corporate code: “If we are good for the UK corporate code, we are good for any corporate code.”

The planned relisting, under which 90 per cent of Metlen’s shares would trade in London while 10 per cent remain in Athens, comes at a desperate time for the London Stock Exchange. The market has endured a dearth of new corporate listings, while several high-profile companies, most notably the Cambridge tech firm Arm, have floated their shares in the US in a quest for higher valuations.

But Mytilineos is still a London bull: “The LSE, even if it is not in its most glorious phase, is still the LSE.”

I push him — why join a market deserted by others? The self-professed Anglophile raises his voice and starts to bang the oak table. “The question is: do you believe in London as a financial hub or not? I do. Do you believe that the City of London, after Brexit, has seen the worst? Yes, I do. Do you think that our presence there as Metlen will help the LSE, together with other companies, to find its previous glory? Yes, I do!” he roars.

The family firm traces its roots to 1908, when his grandfather, also called Evangelos Mytilineos, founded a metals business that forged consumer goods such as lamps. “I am lucky to share his name,” says Mytilineos. It grew to have several hundred employees, becoming a sizeable enterprise that the grandfather was hoping to pass on to his four sons. But then, disaster struck. With the outbreak of the Second World War and the German occupation of Greece in 1941, the company was requisitioned by the Nazis. The war also dispersed the family: three of the sons took to the mountains to try to repel the invaders, while Mytilineos’s father headed to Egypt to fight alongside British troops against the Italian invasion there.

Mytilineos was born in 1954 at a tumultuous time for Greece. His family had moved to Argentina in the aftermath of Greece’s bloody civil war, between 1944 and 1949, in search of a more stable life. But his mother’s homesickness forced the family to return to Athens, where he was born.

The young Mytilineos took to academic study, especially economics and history, which he knew he would use one day to run the family firm. “I was always a good student,” he says proudly.

After an undergraduate degree from the University of Athens, he headed to the London School of Economics for a masters degree in economics. “I didn’t have a lot of time to spend outside of the library,” he laughs.

He took over the family firm in his mid-30s in 1978, when it was a modest metal trader that bought and sold steel and other metals. Inspired by the swashbuckling corporate culture of the 1980s, Mytilineos sought to transform the family firm into a metals and mining conglomerate.

He relaunched the business as Mytilineos Holdings in 1990 and went on an acquisition spree, snapping up copper, zinc and lead mines across Europe. Eager to raise more money for expansion, Mytilineos listed the company on the Athens Stock Exchange in 1995 and three years later hatched Greece’s first hostile takeover, buying a once state-owned construction business named Metka.

The metals business was highly energy intensive, so Mytilineos decided to venture into the energy trade in the early 2000s, setting up power-generation and wind companies. It paid off: energy is now the main moneyspinner for the company, with the recent surge in global energy prices causing its revenues to soar.

Yannis Stournaras, the governor of the bank of Greece, has a lot in common with Mytilineos; they are around the same age and were both educated in the UK. “He’s very simple — he’s a man of work. He’s not a rentier; despite the fact that he has created this giant, he participates every day in everyday business,” says Stournaras of the man from Metlen. “He inspires — he pays a lot of attention to developing skills for staff.”

Is the governor at all concerned that his country’s biggest home-grown firm is about to up sticks to the UK? “It’s now an international company, anyway. So I think he should move away from the Greek borders and get listed in a much bigger market. I don’t think he will abandon Greece,” Stournaras says.

Mytilineos’s most-prized asset is Aluminium of Greece. This is Metlen’s metals-processing plant, 110 miles from the Athens HQ, which extracts aluminium from bauxite, a reddish-brown rock dug up from the company’s mines, a further several hours’ travel away. Nestled in a valley looking out onto the Mediterranean, the plant is the size of a small town — an unyielding rollercoaster of pipes, smoke-belching chimneys and cooling towers. Attached is a port where vast ships moor up to load with tonnes of aluminium for export across the world.

The buildings, the employees’ faces and the valley’s surrounding vegetation are all covered with a thick red tinge from the bauxite. To zip around the vast complex safely and quickly, employees pedal large tricycles with baskets on the back, often filled with small bundles of paperwork.

Mytilineos has a model-village version of the site mounted on the right-hand side of his plush Athens offices. “I am very much sentimentally attached to the place. There are thousands of people working there and I’m very close to them, like first among equals,” the billionaire says, gazing out over the toy town. The complex is one of his favourite places in the world and he has bought a bougainvillea-clad house nearby, which he visits every month.

He also has high hopes for its future. Metlen is in the process of using its sites to manufacture gallium, a byproduct of bauxite that can be used to make semiconductors and solar cells. The EU drafted in Metlen to start manufacturing gallium after China, which dominates the trade in many rare earth metals, shut down its exports last year. Discussing this brings the wannabe statesman into his own: “When the Chinese stopped the exports, it was using gallium and other metals like germanium … as a tool — as a foreign policy tool … As a weapon. It’s like oil or gas, but it’s more important, equally important.”

A London listing may be a big challenge, but Metlen and its cerebral boss have been through testing times before. The company’s share price cratered in the aftermath of the sovereign debt crisis early in the last decade, when international investors pulled money out of Greek equities. “I saw it coming,” says Mytilineos. “By that time, I was seasoned in business and economics to understand that [the politicians were] bullshitting.”

The company decided to pivot by expanding internationally. “We started to export most of our goods, because in Greece, people didn’t have money to pay. It was extremely difficult. And every day, you didn’t know what the next day would bring. That was probably one of the most difficult business periods of my life.”

The ordeal makes the prospect of a relisting look simple by comparison, and Metlen’s chief executive is nonchalant about the whole thing. “I’m in London ten times a year. Now I will be 15, or stay longer. I’m at home in London anyway,” he says.

But the most difficult part of the whole process has been tearing the family name down from the shop. For the first time, Mytilineos becomes emotional and fights back tears. “Sentimentally speaking, the most important issue in the relisting exercise, by a long way, was the change of the name,” he says. “That is the toughest part because it’s an old name. I made sure I keep the name intact as I found it, so that I can give it to my kids.”